The European Union’s poorly co-ordinated arms export policy is undermining Europe’s security, its foreign policy and its defence industry.

The EU’s arms export policy should have three aims. First, arms control, in order to keep arms out of the wrong hands. Second, targeted arms exports to allies and countries that share the EU’s security challenges. Third, supporting the development of European military technology.

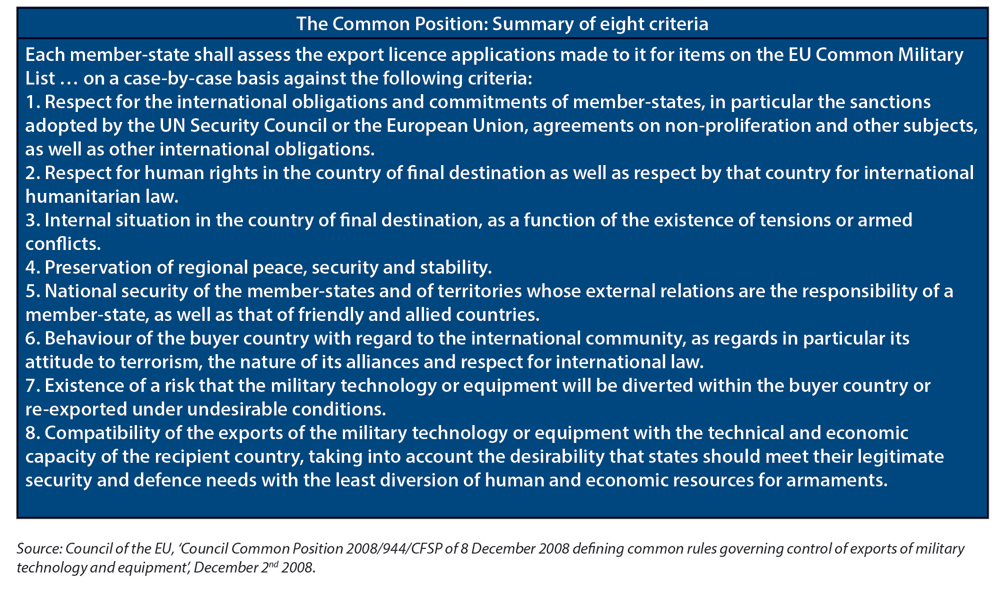

The Union’s current arms export regime, the ‘Common Position’, sets out eight criteria that member-states must test export licenses against, such as respect for international humanitarian law in the destination country. But because defence is considered a matter of national sovereignty, the Common Position is not implemented or enforced at the EU level.

The recent spat over arms exports to Saudi Arabia – Berlin ceased arms exports to the kingdom, to the chagrin of Paris and London – exposed how national arms export decisions are often driven by different political, economic and industrial concerns. Such disunity makes it harder for Europe to help resolve conflicts or influence the behaviour of third countries.

Arms export policies differ across European countries because there is little consensus on the threats to the EU or on the Union’s interests. This has been evident in the EU’s foreign policy towards Syria and Venezuela. In May 2013, the EU’s 28 foreign ministers failed to reach a consensus on renewing the embargo on arms sales to Syria, with some member-states vying to arm rebel groups. And when anti-government protests erupted in Venezuela in early 2017, EU member-states spent months debating whether or not to intervene, allowing the situation to deteriorate significantly before finally agreeing on a sanctions package that included an arms embargo. In both cases, the EU found itself unable to seize its opportunity to alleviate the situation.

Exporting to third countries allows defence companies to enlarge their customer base and create economies of scale. At the same time it raises the bar for European firms to make more competitive products. By combining stricter export controls with more research and development spending, the EU would create incentives for defence companies to improve technology while reducing death, injury and destruction outside the EU.

Member-states will only join forces to develop new military equipment or weapon systems if they trust each other to provide the necessary components in times of crisis – to customers both inside and outside the EU. Without a reliable and consistent arms export policy at European level, the EU’s recent high-profile initiatives to improve European defence capabilities risk falling flat.

A truly common EU arms export policy would require a supervisory body controlled by the European Commission to report violations of the Common Position by member-states. The Commission could refer member-states that refused to follow the rules to the European Court of Justice. But such a radical overhaul would require changes to the EU treaties – and there is no appetite among member-states to surrender their autonomy.

However, there are smaller steps that the EU can take without treaty changes that would more closely align member-states’ arms exports regimes:

specify what constitutes a ‘clear risk’ or ‘serious violation’ in the Common Position, make it explicit that existing licenses can be suspended or revoked, and make reporting obligations more stringent;

help member-states implement stronger ‘end-use’ controls to ensure arms do not end up in unintended hands;

clarify terms in the EU’s regulation on ‘dual-use’ goods (those with both a civilian and military use such as cyber-surveillance technology), and encourage information exchange between member-states;

reach inter-governmental binding commitments to abide by the EU’s toughened export criteria between some member-states, especially France and Germany, which would put greater pressure on laxer member-states.

Together, the EU’s member-states are second only to the US in the volume of arms they export.1 But EU arms export policy is poorly co-ordinated. The divergence is weakening Europe’s ability to achieve its foreign policy objectives, undermining not only its credibility as a principled, values-driven power but also its recent high-profile initiatives to improve European defence capabilities.

Europeans recently fell out over arms exports to Saudi Arabia. Following the murder of Saudi journalist and dissident Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018, Germany decided to suspend all arms exports to the kingdom. Other European countries including Finland, Denmark and Norway had already taken this decision following the devastating Saudi-led intervention in Yemen in 2015. France and the UK, however, sharply criticised Germany and pressed Chancellor Angela Merkel to revoke the decision.

Too often, arms exports are driven by political, economic and industrial concerns, rather than by the EU’s own laws and guidelines. Governments are not only concerned with national security and regional stability, but also with facilitating the exports of domestic defence companies, which generate profits, jobs and tax revenues. Thus the allure of large arms contracts can skew a country’s foreign policy.

The Saudi case underlines the need for a co-ordinated European arms export policy, which should have three strands. The first is arms control: keeping arms and dual-use goods out of the wrong hands, that is, state or non-state actors that could use them to violate international law or create instability.2 The second is targeted arms exports: selling military equipment to actors with shared security challenges. The third strand is the arms industry itself: a consistent, predictable and shared arms export policy would help support European capability development and foster a stronger European defence industry.

Arms exports have been repeatedly excluded from EU treaty provisions. Member-states are unwilling to surrender their autonomy in this area of defence policy, which is guarded as a matter of national sovereignty. Attempts by the EU to co-ordinate national policies have repeatedly failed. The Council of the EU is currently reviewing the EU’s guidelines on arms exports: now is the time for a closer look at the EU’s arms export regime.

This policy brief argues in favour of an effective common European arms export policy, examining its potential to support foreign policy through several case studies, and how it can support the EU’s ambition to build a strong European defence industrial base. We assess the EU’s current arms export regime, and ask whether a greater role for the EU in arms export regulation is possible and compatible with member-states’ interests. Finally, we make recommendations on how Europe’s arms export policy could be improved.

Why does the EU need an arms export policy?

A genuinely common policy would help prevent weapons made in the EU from being used to undermine stability or violate international humanitarian and human rights law. It would also help the EU to promote regional stability, protect allies and friendly states, and strengthen Europe’s defence industry.

1. Control: Preventing weapons falling into the ‘wrong’ hands

By restricting arms supplies, the EU can attempt to change a state’s behaviour. Arms embargoes can constrain aggressive behaviour by depriving a country of military resources. Restricting arms exports can also send a strong signal condemning human rights abuses or violations of international humanitarian law.

Arms embargoes can constrain aggressive behaviour by depriving a country of military resources.

Politicians sometimes oppose arms embargoes on the basis that the target state will simply switch to an alternative, possibly less ethical, supplier.3 But switching suppliers is costly, and may leave the target state with multiple incompatible weapons systems. Such obstacles might end up delaying or constraining its behaviour. At the very least, an embargo stops the Union contributing to a humanitarian crisis or atrocity.

The effect is much greater if member-states work together. Take Germany’s 2018 ban on arms exports to Saudi Arabia. There are good reasons for Europeans to stop exporting arms to countries like Saudi Arabia that are involved in an active conflict with desperate humanitarian consequences. The debate in Germany, however, did not centre on the violation of the EU’s arms export regime, the 2008 Common Position, but instead on pacifist principles and the consequences of German history.4 The episode was a missed opportunity: Berlin chose to take a stand on its own rather than work with other EU member-states to arrive at a European position.

At the same time, the impact of arms embargoes should not be overstated. Alone, they are ineffective in changing state behaviour. Arms embargoes are particularly poor at preventing human rights abuses and crackdowns on democracy. The most effective embargoes are usually accompanied by other measures – economic sanctions hit countries far harder.5

2. Export: Putting weapons in the ‘right’ hands

Europeans sometimes export to strategic partners or allies in crisis-prone regions in the hope of contributing to regional stability. For instance, the German government is donating 50 Marder tanks to Jordan to protect its borders against Islamist militant groups.6

Exporting arms to conflict zones is a risky strategy, and should always form part of a comprehensive support programme, including training security forces about how to use the arms in line with international law. Supplying arms can alter regional dynamics in unpredictable ways, making a previously militarily weak country more belligerent, as seen with US arms sales to Iran in the 1970s.

European arms and equipment can, however, be exported to support countries struggling with globally significant security challenges. Maritime security, for instance, is crucial for Europe’s prosperity and stability: 50 per cent of EU external trade is transported by sea, and maritime crime in the forms of theft, smuggling, piracy and terrorism is widespread. EU member-states can assist countries in their attempts to combat piracy by selling them naval equipment.

Arms exports can also ensure that European allies and partners maintain technological parity with or superiority over shared adversaries. This strategy is already being pursued in Asia. To counterbalance Chinese dominance in the region, the US and some EU countries are exporting arms to countries like Indonesia: the Dutch company Damen, for example, exported two Sigma naval frigates to the Indonesian navy in 2017 and 2018. Arms exports can also increase interoperability and make it easier to conduct joint operations with partners.

3. Supporting the EU’s defence industry

If Europe is to become a credible defence player, it needs to have a strong defence industry. But a competitive defence industry requires a coherent and credible EU arms export policy.

First, EU defence policy can help companies become less dependent on exports, and more selective about who to export to. To cope with the relatively low national-level defence spending in Europe in recent years, and with the fragmentation of the market, companies have prioritised commercially attractive dual-use capabilities – which can be used for both military and civilian objectives – or have shifted away from their home market and focused instead on exports. A business model that relies on exports means that restrictions on arms exports immediately endanger jobs. And since European countries tend to ‘buy national’, the main export markets for European arms are often in countries outside the EU, rather than in other member-states. As a result, European industries at times prioritise the capability needs of non-European customers over those of EU states.7

At the same time, pursuing a strict ‘buy EU’ policy would make it more difficult for European military forces to fill their capability gaps in time, since the EU’s defence industries are not able to cater to all of Europe’s equipment needs.8 The more units of goods with high development costs that are produced, the lower the average cost of each unit. To achieve such ‘economies of scale’ in defence production, European industry has an interest in enlarging its potential customer base through exports. Plus, keeping the European market open and exporting to partner countries (such as democratic, law-abiding NATO members) would also raise the bar for European companies and lead to more competitive products.

In a best-case scenario, the EU would stimulate defence research and development spending from member-states, which would benefit European industries and simultaneously relieve at least some of the pressure on them to find export customers and prioritise their requirements over those of European security.

Second, member-states’ arms export policies need to be reliable and consistent in order to engage in joint capability development. The EU has devised a range of new initiatives to improve its defence capabilities. Among the most high-profile of these new initiatives are the Co-ordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD), the European Defence Fund and Permanent Structured Co-operation (PESCO). All of these aim to encourage member-states to co-operate on capability development.

The EU envisages that the process will work as follows: the EU institutions together with European governments identify Europe’s capability gaps and opportunities for joint capability development through CARD; they agree on a list of military equipment that is needed in Europe (the so-called Capability Development Plan); a group of PESCO members decides to develop an item together; and that group gets co-funding from the European Commission via the defence fund. But so far, the EU has not yet developed a plan about what to do when these member-states cannot agree on arms export rules.

Germany’s decision in the autumn of 2018 to suspend all arms exports to Saudi Arabia indicated just how much of an obstacle arms export policy could become to joint capability development. In 2018, Berlin put a halt to the sale of already assembled items, such as patrol boats, as well as German-produced components used by other companies across Europe. The freeze held up the delivery of Meteor air-to-air missiles to Saudi Arabia.9 The missiles are produced by the European company MBDA (jointly owned by Airbus, BAE Systems and Leonardo), but the propulsion system and warheads are built in Germany. German components are also needed to maintain European products after delivery, such as the Eurofighter Typhoon planes, produced jointly by the UK, Germany, Italy and Spain. Germany’s allies criticised the unpredictability of Berlin’s arms export policy and warned that European defence companies would resort to producing ‘German-free’ goods in the future.10

Member-states will only come together to create new military equipment, like the next European fighter jet, if they can rely upon one another for the supply of components. Without a common arms export policy, jointly-produced systems will always be vulnerable to one of the partners introducing export controls on one or more of the potential purchasers.

How does the EU export and control arms?

The EU’s arms export regime is fragmented, and based on three layers of law: international, EU and national. The regime is made up of several legislative instruments, which are monitored by different EU institutions. And while the EU sets out basic tenets for arms exports, licensing and regulation is determined at the national level, resulting in 28 national licensing systems and sets of rules.

Although arms exports ultimately remain a matter of national competence, EU member-states have agreed to “high common standards” and “convergence” in managing arms transfers.11 There are two parts to this commitment. First, the European Council adopted the Common Position on Arms Export Controls in 2008, which defines common rules governing the control of exports of military technology and equipment. Second, all member-states are party to the international Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), which establishes the “highest possible common international standards” for the global arms trade. The ATT was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2013 and entered into force in the EU in 2014. Both the ATT and the Common Position are legally binding, and regulate exports of conventional weapons.

The Common Position sets out eight criteria against which member-states must test export licences, including respect for human rights and international humanitarian law in the destination country.

However, the regulation of arms exports is a national competence in the EU. Article 346 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union affirms that a member-state can take measures in relation to arms trade and production to protect its security interests, and that the EU treaties do not apply to such measures. Article 346 cannot in principle be invoked for economic reasons such as to protect national industries and jobs. But the reality has often been different.12

The EU encourages convergence between member-states’ export policies through information-sharing on export licences. National export authorities attend monthly meetings of the Council’s Working Group on Conventional Arms Exports, known as COARM, where they consult one another and exchange sensitive information on licences they have denied. COARM uses the EU’s electronic communication network to allow member-states to notify one another in real time when an export licence has been turned down (around five to 10 times per day).13 The denial notifications are collated in a central EU database. Once a year, member-states submit their export data, which is compiled into a report. COARM has also developed a user’s guide which outlines best practices for applying the eight licensing criteria to arms exports.

If it were properly implemented, the Common Position would be one of the one of the strongest international arms export frameworks in the world. However, member-states often fall far short of their obligations under the Common Position and fail to apply its criteria to their export decisions. France has refused to incorporate the eight criteria into its domestic legislation.14

Countries often fall short of their obligations under the Common Position and fail to properly apply its criteria to their exports.

The Common Position says licences should be granted on a case-by-case basis, so national authorities assess whether a specific weapon export violates the eight criteria. But testing exports in isolation makes it easier for authorities to avoid acknowledging the broader context and cumulative effect of arms exports. Thus a European country may decide to export a weapon to a repressive regime that is committing abuses of international human rights or humanitarian law if the authorities judge that those weapons will not be directly used to commit those abuses. For instance, the UK government has continued to arm Saudi Arabia, even after the kingdom became engaged in a bloody conflict in Yemen in 2015, and despite evidence from the UN that the Saudi-led coalition was violating international humanitarian and human rights law.15 The then international trade secretary, Liam Fox, defended the government’s decision to export to the Saudis, arguing that it is the government’s job to conduct “a prospective and predictive exercise as to whether there is a clear risk that exports might be used in the commission of a serious violation of IHL in the future”.16 Decisions about large-scale arms exports are taken at the highest political level, meaning that judgements will be political rather than guided by the details of the Common Position.

The Common Position is also poorly enforced. Although it is legally binding, member-states are free to decide how they implement it, and there is no formal mechanism to sanction non-compliance. National governments could be taken to court if their export decisions violate the Common Position. The European Council’s legal service says that national courts can use the Position as a legal basis for prosecution, though this rarely happens. But with few exceptions, the Treaty on European Union (TEU, 2009) gives the European Court of Justice (ECJ) no powers in relation to common foreign and security policy. As a result, export authorities can be confident that there will be no material consequences for a loose interpretation of the Position.

Instead of relying on EU oversight, member-states tend to draw up memorandums of understanding ahead of joint capability projects, designed to prevent any one country from blocking sales of arms that other partners want to make. But even these agreements do not legally bind their signatories – Germany broke some of them in 2018, for example.17 In spite of the EU’s Common Position, each country currently maintains the final say over where its arms are exported to, and enjoys quite a bit of flexibility in that decision.

Sales of military goods within the EU are regulated by the Intra-Community Transfers Directive (2009). Its aim was to facilitate trade of conventional military goods within the EU. Member-states have implemented the directive via their national laws, but it has had limited success. As it stands, few defence companies have taken the opportunity to become certified, as it is not considered worth the cost and effort.18

Goods that have both a military and a civilian application – dual-use products – do not fall under the Common Position. Controlling the trade of these items is an EU competence, so they are regulated as part of the Union’s common commercial policy under Council Regulation 428/2009 (Dual-Use Regulation). As a result, and unlike conventional arms, dual-use items fall under the ECJ’s jurisdiction. However, cases involving these products tend to come before national courts – no such case has ever been tried at the ECJ. The EU is the only region in the world with a shared legal basis for controls on dual-use exports.19

At its most stringent, arms export control can take the form of an arms embargo on specific states or non-state actors. The Union has imposed arms embargoes on 38 such actors since 1996. The legal basis is set out in the TEU which states that sanctions (‘restrictive measures’) can be issued to pursue common foreign and security policy goals, such as the advancement of democracy, the rule of law and human rights. The EU can also impose sanctions under a UN Security Council mandate.

The Council and the European External Action Service (EEAS) are the two key institutions in the arms embargo process. The EU’s High Representative can initiate an embargo. The Council then adopts a decision (with the advice of the EEAS), which must be unanimous.

If the embargo is part of a broader sanctions package that involves economic or financial measures, then the High Representative (and in the case of dual-use items, the European Commission) drafts an implementing regulation, and the Council adopts the regulation by qualified majority voting. The decision is legally binding on member-states, which must then implement the embargo via national legislation.

The Union’s sanctions packages (other than those that are mixed with UN measures), including arms embargoes, are adopted for six months or a year. Towards the end of the period, the Council must reach consensus in order to prolong or adapt the embargo. There are very few exceptions, for instance, the Iran nuclear deal which sets specific expiry deadlines. The Council must also reach consensus in order to terminate sanctions before the specified end date.

Like the Common Position, arms embargoes are often poorly implemented and enforced in EU member-states. The EU’s foreign and security policy sanctions committee monitors EU sanctions but has little control over how they are implemented by member-states.

The following three cases – Saudi Arabia, Syria and Venezuela – show how co-ordination at the EU level, or lack of it, has played out in previous arms exports decisions.

Saudi Arabia

In 2015, the Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman launched a military intervention in Yemen. The Houthis, a Shiite tribal group, had taken control of the country’s capital, Sana’a, and forced the resignation of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi and his government – which had been backed by the Saudis. Saudi Arabia presented the incursion as necessary to control Iranian influence on the Arabian Peninsula, exaggerating the extent of Iranian support for the Houthis.20 The Saudis formed a coalition of nine other Sunni Arab countries: the UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Jordan, Sudan, Egypt, Morocco and Senegal.21 The coalition wants to restore the Hadi government and provides financial and military support to the Yemeni army and proxy armed groups. The US, UK and France provide the coalition with arms, military equipment and training. The conflict has left 22 million people, three-quarters of all Yemenis, in need of humanitarian aid and protection.22

Member-states exporting arms to Saudi Arabia could themselves be in breach of international humanitarian law.

The Arms Trade Treaty, the Common Position and national legal frameworks all predicate arms exports upon respect for international humanitarian law, which governs armed conflicts, in the destination country. EU member-states have an obligation to take all possible steps to safeguard respect of international humanitarian law by the warring parties in Yemen.23 But UN experts have concluded that the governments of Yemen, the UAE and Saudi Arabia are responsible for numerous violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.24 Member-states exporting arms to Saudi Arabia, in the knowledge that the equipment could be used to violate international humanitarian law, could themselves be in breach of international humanitarian law.25 The European Parliament has stated that member-states that supply weapons to the Saudi-led coalition are “in violation” of the Common Position and called for an embargo, though this opinion has no legal weight.26

France and the UK were the second and third largest suppliers of arms to the Saudis from 2013-17, after the US. The French and British governments have insisted that arms exports to the coalition are lawful and strategically important. The logic for supporting the Saudi-led coalition is the need to counter-balance Iranian efforts to dominate the region. But given Saudi Arabia’s tilt towards an erratic, aggressive foreign policy, the usefulness of the Saudis as a regional partner is questionable.27 The UK Court of Appeal recently ruled that the British government’s decision-making process for export licences for billions of pounds’ worth of arms to Saudi Arabia had been unlawful. In its judgment, the court said the British government failed to assess whether the Saudi-led coalition had violated international humanitarian law during the Yemen conflict. For now, the British government cannot grant new licences to Saudi Arabia until it has re-evaluated its existing export licences in line with the law.28 The UK government will appeal the decision.

The UK and France believe Saudi Arabia is an important strategic partner in the region, and fear the lost business if they stop arms exports to the kingdom. But other member-states have imposed their own national arms embargoes on the kingdom in response to the situation in Yemen and to the murder of Khashoggi. Finland, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Wallonia region in Belgium and the Netherlands have stopped licensing exports. Sweden refused to renew its military co-operation with Saudi Arabia in 2015, and the Flemish parliament in Belgium rejected a request for military supplies in 2016.

Alleviating the humanitarian crisis in Yemen and supporting European interests in the region requires a co-ordinated approach, however. The Saudi-led intervention in Yemen poses a serious danger to the stability of the region, and thus to European interests there. The Yemen crisis could lead to more migration from the Middle East towards the EU. The current power vacuum in Yemen and the dire humanitarian situation there have bred instability, allowing extremist organisations like al-Qaeda to flourish. The EU is worried that conflict might spill over to other countries, after Europe has invested heavily in promoting stability and security in Egypt, Iran, Syria, the Gulf of Aden, and

the Horn of Africa. Europe’s divergent arms exports policies are thus undermining the continent’s security and credibility.

Syria

Much like the Yemen conflict, the Syrian civil war has exposed Europe’s lack of common foreign policy, as exemplified by diverging arms export policies.

Syria descended into civil war after President Bashar al-Assad brutally cracked down on pro-democracy protesters in April 2011. The EU responded by imposing sanctions on Syria, including an embargo on the sale of arms and military equipment to all actors (other than humanitarian workers). The embargo was fleshed out by Council regulations in 2012, which banned specific items such as telecoms interception equipment.

Although lifting the embargo did not significantly alter the situation on the ground, it revealed Europe’s disunity.

In September 2012, when Assad looked dangerously close to victory, the UK and France began to agitate for lifting the embargo. The UK and France wanted to arm the Syrian rebels, whom they saw as the moderate opposition to Assad. They argued that strengthening the Syrian rebels would protect civilians, ‘level the playing field’ and help facilitate a diplomatic solution by forcing Assad to the negotiating table.29 Austria, the Czech Republic, Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden strongly opposed lifting the embargo, arguing that this could exacerbate the conflict and that weapons could be diverted to al-Qaeda.

In May 2013, following a 13-hour meeting of European foreign ministers, the EU lifted the arms embargo for the Syrian rebels. The 28 foreign ministers failed to reach consensus on renewing the arms embargo. Instead, they agreed a weaker political commitment not to supply arms, and then High Representative Catherine Ashton attempted to gloss over the disunity. “Member-states may take different decisions – that doesn’t mean we’ve lost the capacity to have a common foreign policy”, she said. The Austrian vice chancellor and foreign minister, Michael Spindelegger, lamented: “It is regrettable that we have found no common position”. The Council promised to review its position before August 2013. It did not.

In June 2013, a UN report detailed war crimes and abuses by Syrian opposition forces (though to a lesser extent than by government forces and affiliated militia). The report urged the international community to restrict arms transfers “given the clear risk that arms will be used to commit serious violations of international human rights or international law”.30

In 2014, Germany, the UK and Finland issued 16 licences for “vehicles”, “chemical, biological or radioactive agents” and “armoured or protective equipment”, worth €1.5 million – some of which were destined for UN-mandated or other international missions.31 This was just a slight increase from the 10 licences the years before.32 In the end, there was no reporting of European member-states directly supplying the rebels – although it later emerged that European weapons had inadvertently reached armed rebel-groups. Lifting the embargo did not significantly alter the situation on the ground, though it did reveal Europe’s disunity.

Venezuela

Since Venezuela descended into crisis in 2010, Europe has struggled to speak with one voice. The EU’s High Representative for foreign and security policy Federica Mogherini has often been limited to making declarations when member-states could not reach a consensus on sanctions or who to designate as the country’s legitimate government.

After months of anti-government protests, President Nicolás Maduro was re-elected in a rigged election in the autumn of 2017. The EU’s member-states spent months arguing over how to manage the unfolding crisis, with disputes over the EU’s right to intervene and encourage a change of regime. The EU was unable to reach a unanimous decision on sanctions, in part because Greece and the populist Five Star Movement within Italy’s coalition argued that sanctions interfered in Venezuela’s sovereign affairs. Only in November 2017 did the EU adopt sanctions on Venezuela and call for free and fair elections. The restrictive measures included asset freezes and travel bans on individuals, as well as an arms embargo, including on equipment that could be used for internal repression or monitoring. In an official communication, the Commission later argued that this delayed decision followed “a further substantial deterioration of the situation on the ground”.33

Member-states continue to prioritise short-term financial and industrial concerns above common EU foreign and security objectives.

Member-states’ arms policies towards Venezuela have often been guided by economic and industrial interests, rather than by concern for regional stability. However, most of Venezuela’s military equipment is procured from Russia and China (82 per cent), with EU member-states playing a minor role (11 per cent, most of which came from Spain, the Netherlands, France and Germany).34

Before the embargo, European member-states sold arms to Venezuela despite rising regional tensions. In 2008 the Chávez regime threatened to send tanks, troops and Russian combat aircraft across the Colombian border – threatening regional stability and even European territory like the (then) Netherlands Antilles. That did not stop EU countries approving seven more arms export licences to Venezuela in 2009 than the previous year. That included a huge contract for almost a billion euros worth of warships from Spain – Madrid’s largest ever arms contract at the time and licences for fire control systems and naval equipment worth €28.3 million from France.35 The risks of Europe providing such equipment were brought into focus years later in December 2018, when one of the Spanish frigates sold to Venezuela intercepted a Norwegian oil exploration vessel (which was undertaking a survey on behalf of the US company ExxonMobil) off the shore of Guyana and forced it to flee the area, in an attempt by Venezuela to claim its sovereignty over contested waters.36

As late as the first quarter of 2018, the Spanish government authorised the sale of €20 million worth of tank parts to Maduro’s government – even though the embargo had started in November 2017. The authorisation was technically permissible because the embargo includes an exemption for contracts that were already concluded. The Spanish government said the contract for the sale had been signed before the embargo, and that it was just the political approval that came later. But the deal would have been halted without this political approval. The latest Spanish sale shows that member-states continue to prioritise short-term financial and industrial concerns rather than common EU foreign and security objectives – in spite of the clear risks involved.

Is a greater role for the EU in regulating arms exports possible?

Europe needs more co-ordination when it comes to arms exports. Divergent arms export policies undermine Europe’s common foreign and security policy goals. Sanctions taken at the individual country level are ineffective. When Europeans act in unison, the impact of their foreign policy is multiplied, especially when their arms export policies are integrated into broader EU policies towards particular regions or conflicts.

There are radical, and for now unrealistic, ways of bringing about a common European arms export policy. For example, to ensure that member-states adhere to the Common Position, the EU would have to introduce a mechanism to hold governments accountable for breaking the rules. Or if member-states agreed to give up some national decision-making authority over arms exports, the EU could establish a supervisory body controlled by the Commission or the High Representative to report violations of the Common Position by member-states. The Commission could refer member-states that refused to follow the rules to the ECJ.37 Such a new body would require a change to the EU fundamental treaties and therefore unanimity among EU member-states, however.

At present, there is little appetite among member-states (including Germany) to give up decision-making power in this field. Anne-Marie Descôtes, the French ambassador to Germany, recently dismissed the idea of Europeanising arms exports as a cop-out and an attempt to pass responsibility to European institutions.38 She argued that it would be an unparalleled transfer of sovereignty and an unacceptable violation of Article 346. Her reading of the mood in Europe is accurate. But the EU’s plans to build a ‘defence union’ could open a window of opportunity for ‘more EU’ in arms export policy.

At present, there is little appetite among member-states to give up decision-making power on arms exports.

The EU’s recent defence initiatives represent a qualitative shift in the way the EU gets involved in defence. For years the European Commission has kept out of the defence realm, long considered a bastion of national sovereignty. Now, it has slowly begun to carve out a role for the EU in order to address some of the underlying problems that beset European defence technology and industry.

The proposed introduction of the European Defence Fund into the next EU budget is a step towards a greater EU role in capability development. The fund’s regulation states that Commission funding should have no effect on exports of arms developed with the help of EU money – the result of rigorous opposition from member-states, in particular from France, to any EU authority over exports.39 The regulation also stipulates that EU money cannot be used to fund small and light weapons that are meant mainly for export purposes, when no member-state has expressed a requirement for the weapon. And the regulation says member-states have to notify the Commission of any export of EU-funded kit to a non-EEA country;40 and, if that export “contravenes the security and defence interests of the Union and its member-states”, the money provided under the fund must be reimbursed. The security and defence interests of the Union are not laid down anywhere in a binding manner. But in the future, the Commission could potentially refer back to the regulation to expand its involvement in arms export policy.

The European Parliament will also want to become more involved in the EU’s defence planning and capability development process, and to have greater oversight of the defence fund. When the fund was first put to a vote in April 2019, 328 EU parliamentarians voted in favour of it and 231 voted against.41 In addition to those who opposed a greater EU defence role on principle, MEPs who opposed the fund questioned in particular the defence industry’s involvement in the drafting of the Commission’s proposal, as well as the Commission’s plans to spend EU money on disruptive technologies – potentially including artificial intelligence, robotics and unmanned systems – which some MEPs consider problematic from an ethical perspective. The Parliament currently has very limited control over the EU’s defence efforts, but now that the EU budget is being used for capability development, this could change in the future.

The Commission is also using its control over the trade of dual-use goods to expand its influence over arms exports. The institution recently tightened the regulation of cyber-surveillance equipment, which could bolster its ability to add items to the dual-use list, further embedding the Commission in defence matters. The institution emphasises the fact that European defence markets deal with many dual-use goods, thus strengthening its basis for challenging member-states that invoke Article 346.42

There are thus some signs of an increasing role for the EU in defence industrial policy. But treaty reform and an overhaul of Europe’s arms export regime are still a long way off. Plus, some fear that a harmonised policy would necessarily have to settle for a ‘lowest common denominator’ level of restraint, and be less restrictive than those of many member-states currently. And some NGOs and civil society organisations worry that giving greater powers to the Commission, which is less accountable than member-states’ governments, would make the system still less democratically accountable.

Without a functioning common European arms export regime, the EU is unlikely to be able to live up to its full potential in terms of foreign policy. But in the meantime, there are still ways in which the EU could maximise the impact of export and embargo decisions, strengthen the European defence market, and ensure that arms exports are in line with European values and interests.

Recommendations

1. Improve the Common Position

A review of the Common Position began in 2018, and is ongoing in COARM. Reviewers are considering how to improve the wording of the Position; possible changes to the users’ guide, including an e-licensing system for military goods; and adapting the annual report into a publicly available online database to improve transparency. Any change to the Common Position will require unanimity.43

COARM should take seriously the gaps and failings of the current arms export regime.

COARM should take seriously the gaps and failings of the current arms export regime. Reviewers should clarify some terms – on which the recent UK Court of Appeal case turned – such as ‘clear risk’, ‘might [be used]’ and ‘serious violations’. COARM could also consider shifting the emphasis in the Common Position away from the current narrow, functional approach, where the licensing authority tests whether that particular weapon system could be used to violate international human rights or humanitarian law, towards a more holistic view of the situation in the destination country. The Common Position should also make it explicit that existing licences can be suspended or revoked if the export authority so decides. This would confirm that compliance with international law takes precedence over reliable supply, and might avoid decisions like that of the Spanish government to authorise the sale of tank parts to the Maduro government in 2018.

The Common Position sets out member-states’ obligations to report annually on the export licences they have issued. But many member-states, including France, the UK and Germany, still fail to submit full reports on time. The EU should establish strict reporting deadlines and standardise the format of these reports – some member-states compile their statistics differently, and some use national classifications of military equipment rather than the EU Military List. Reporting obligations should include actual deliveries, which would give a more complete picture than just reporting export licences – this could for instance signal that a regional balance might be disturbed by a sudden influx of weapons. If one member-state feels that another has authorised an export in violation of the Common Position criteria, it could ask the exporting state to share its risk assessment in confidential channels, showing how its exports fit with the criteria.

Some countries struggle to implement even the current reporting obligations, due to a lack of resources or know-how. COARM should organise peer review meetings where governments can exchange best practices on how to gather data from industry.44 The peer review process could also be broadened, so that member-states could discuss how they implement the Common Position at the national level: whether it has been transposed into national legislation, and what guidance is available for licensing authorities.

2. Implement stronger end-use controls at the EU level

Licences for the export of military equipment should only be issued once the seller knows who will use the weapons in the destination country and what for. But any arms export regime runs the risk of diversion, where weapons can, and do, end up in the wrong hands. This is particularly true for small arms, which cause the largest share of human casualties in internal and cross border conflicts; frequently contribute to their violent escalation; and, in the hands of criminal groups, can impede economic and social development.45

A 2017 report found that more than 30 per cent of arms used by IS fighters in Syria and Iraq came from Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Germany.46 In spite of clear diversion risks, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Romania supplied weapons to Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the UAE and Turkey. EU countries licensed €1.2 billion worth of assault rifles, mortar shells, rocket launchers, anti-tank missiles and heavy machine guns between 2012 and 2016.47 This was in the face of evidence suggesting that the weapons could end up with armed rebels and Islamist groups operating in Syria and Iraq, including those responsible for human rights abuses, like Ansar al-Sham, Jabhat al-Nusra (affiliated with Al-Qaeda), and the so-called Islamic State. Given that military components manufactured in Central and Eastern Europe were not compatible with equipment already in service with Saudi forces, it should have been even clearer that there was a risk of diversion. These weapons sales may have violated national, EU and international law.48

European countries have a responsibility to ensure none of their arms end up in the wrong hands. To accomplish that, governments can employ end-use controls, where the recipients have to agree not to re-export the weapons or to pass the weapons on to another user within the country without approval by the seller; and to destroy the weapons that are being replaced by the imported arms (rather than, for example, selling them to a third party).

European countries have a responsibility to ensure that none of their arms end up in the wrong hands.

Experience shows, however, that compliance with these rules is poor. For example, German G36 assault rifles exported to the Mexican government in 2013 subsequently found their way to Mexican police in states at high risk of violence and not covered by the export licence. The rifles are suspected to have been used in the high profile 2014 kidnapping and apparent murder of 43 students from a college in Iguala in the south of the country. The German arms seller Heckler & Koch has since been fined by a German court.

The German government has taken steps to ensure better compliance with its end-use regulations. For example, Berlin introduced post-shipment controls for small arms and light weapons in 2015, which can involve spot-checks once the arms have been dispatched.49 The first on-the-spot controls to verify the final destination of small arms were carried out in recipient countries India and the United Arab Emirates in 2017.50 A few European countries, including Finland, Sweden and Switzerland, have similar regulations or plans to introduce them.51 Others, like the UK, instead rely on their diplomatic connections and resources in the buyer country to prevent exported weapons ending up in the wrong hands.

The EU could explicitly encourage and support member-states to implement their own post-shipment controls. End-use controls are difficult to implement: they require significant financial, legal and human resources, as well as political leverage in the buying country. EU resources, such as expert teams made up of Commission or EEAS staff, dispatched to EU delegations in the buying country, could be employed to help with controls. This would have to be pre-negotiated and included in the contract signed by the purchaser. And it would require the EU to find solutions for confidentiality issues that arise with sharing export information with EU staff, as well as investment in staff with the expertise to identify weapons. But it could become a good instrument to keep purchasing countries honest and to discourage exporters from proceeding with sales where there is clear risk of diversion.

3. Tighten and revise dual-use regulations at the EU and national level

The Dual-Use Regulation (2009) is also under review. During the Arab Spring in 2010-2012, European and American companies exported cyber-surveillance technology to repressive Arab governments. That prompted the European Parliament to call for tighter controls on surveillance technology, which is classified as dual-use. In 2016 the European Commission proposed strengthening the Dual-Use Regulation to include cyber-surveillance technology, and the European Parliament argued for the inclusion of human rights considerations, calling on the Commission to add clear criteria and definitions to the regulation that would protect the right to privacy, data protection and freedom of assembly. The Commission proposal included an EU-specific list of dual-use items52 and the ‘catch-all’ control, which would mean the export of any item could be denied if it might be used to violate human rights.

After a lengthy review process, the Council Working Party on Dual-Use Goods removed the references to cyber-surveillance technology and human rights. This was due to criticism from industry, which was unhappy with the ‘catch-all’ idea, which would place legal liability on defence companies. Some member-states were also concerned that an EU-specific list would affect competitiveness, as the Union would be going beyond internationally accepted standards.53 The Council must now negotiate an agreed text with the European Parliament. Whether or not the new European Parliament will accept this diluted version of the recast regulation remains to be seen.

The EU should establish clear criteria and guidelines for assessing whether to export dual-use goods. As it stands, there is too little clarity on important terms at the EU level, leading national authorities to apply the regulation inconsistently. The EU could also encourage an information exchange between member-states, where authorities can share how they implement the regulation – from how the authority understands specific terms, to the penalties applied, to how licences are issued.54

The EU should strengthen the reporting procedure, requiring member-states to report licence denials, and the number and type of licences that have been approved. Member-states should be obliged to make this information public. To relieve the burden on member-states, authorities could just publish data on exports of cyber-surveillance technology, rather than on all dual-use export items.55

4. Expand inter-governmental agreements

Even at the inter-governmental level, the lack of agreement on arms export policy prevents collaboration. Pending an EU-wide agreement, a practical way to increase harmonisation of EU arms exports could lie in agreements between small groups of member-states.

A way to increase harmonisation of EU arms exports could lie in agreements between small groups of member-states.

In 2000, six EU member-states – France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the UK – signed the Farnborough Framework Agreement, to improve consultation and co-operation on defence. The framework discusses simplifying and harmonising the signatories’ export licensing procedures, and even developing common instruments.

It is an EU adage that nothing can happen without compromise between France and Germany, and that such a compromise can then be applied to the rest of the EU. In 2019, France and Germany signed the Aachen Treaty, a follow-up to the 1963 Elysée Treaty, pledging deeper co-operation between the two countries. They promised to develop “a common approach to arms exports with regard to joint projects”.

In the months since the treaty was signed, Paris and Berlin have also signed a supplementary agreement specifically on the subject of arms exports.56 They agreed that for jointly developed systems – such as the planned European fighter jet – they would inform each other, well in advance of formal negotiations, of any opportunity for sales to third countries. They promised not to oppose the other’s exports “except on an exceptional basis, where their direct interests or national security are compromised”, which again leaves room for each country to fall back on national sovereignty concerns. If there is disagreement over an export, France and Germany plan to hold “high-level talks” where the state opposing the export does “everything possible” to propose alternative solutions. They also agreed on provisions to prevent whole European production lines being stalled because of a national freeze on the export of components. Components produced by one country and incorporated into weapons systems by another will be subject to the de minimis principle: so long as the contribution of that component to the overall system remains below a percentage jointly determined beforehand, the country producing the component guarantees authorisation of the export.

Arms exports provisions agreed by the two frontrunners could be extended to include other countries’ arms exports, or member-states could sign similar agreements between themselves. This government-led process could gradually develop to make arms export rules more predictable throughout the EU. However, to strengthen rather than erode EU foreign policy objectives, these agreements would have to go much further than the one proposed by Berlin and Paris, and include a binding commitment to abide by the EU’s export criteria.

The latest bilateral agreement between Paris and Berlin is very similar to the Debré-Schmidt agreements, signed in 1971 by the two countries’ then defence ministers, which successfully governed exports of jointly developed arms until Germany decided to ban exports to Saudi Arabia. This indicates that the issue is not necessarily the lack of agreements, but rather the lack of a common view of the threat environment.

Conclusion

Europe’s diverging export policies are harming the EU’s interests and credibility. Without stronger co-ordination at the EU level, Europe’s ability to protect its security is diminished, and the Union runs the risk of its member-states violating international law and being complicit in human rights abuses and other atrocities.

A stronger, unified arms export policy is also vital for EU ambitions to develop a European defence industry. Joint European capability projects will perpetually stumble when governments run into disagreements on export rules.

However, before a common arms policy can be agreed, EU member-states must first reach a shared analysis of any given conflict and establish what the EU’s interests are. This often proves difficult. For instance, EU member-states have different views on whether supplying weapons to Saudi Arabia will help stabilise the Gulf region, and how exports might affect European security. At the heart of the issue lies a lack of consensus on threat perception and strategic assessment. And many member-states think in terms of national efforts to protect national security, rather than considering that their national security is rarely distinct from wider EU and European security. Lucrative arms contracts for national defence industries and preserving or creating domestic jobs also generate pressure to interpret the Common Position liberally.

A common and enforceable EU arms export regime, including a sanctions mechanism and supervisory arms control body, should be the goal. Conversations with EU officials and industry figures make it abundantly clear that this is a long way off. But the development of EU defence initiatives and the increasing role of the Commission in defence policy suggest the first tentative steps towards this end may be taking place.

Even if an overhaul were legally possible without consensus, it would be unwise. EU member-states should attempt to reach a shared view on the security context of arms exports, improve the wording of the Common Position and agree on the format of reporting by member-states, tighten dual-use regulation and end-use controls, and reach inter-governmental export agreements. Europe’s security will benefit if the EU can keep moving towards convergence on arms export policy.